View of The Rock from the base. East side.

LESSONS IN REVERSE

Sitting in the driver’s seat after she completed the backing test, Donna turned to Mr. B. sitting on the bench seat beside her.

“I hate you!” she growled.

It’s possible, possibly even probable, that Donna slapped at Mr. B. with both hands, tiny little slaps. I was one of two students sitting in the backseat that day, but I can’t recall the scene one way or the other. However, I do remember teenage Donna as being able to easily express her feelings.

Donna, a sweet girl who loved Jesus more than anything else, didn’t really hate-him, hate-him, but she certainly did not like Mr. B. at all after that driving test dragged her up, around, and down this rocky hill of anxiety. Backwards.

Like Donna, many of us in the class carried a stone in our stomachs after Mr. B. told us toward the end of our ninth grade, year-long driving class, that part of our final grade would be measured by our ability to back the car around Pawnee Rock State Historic Site.

Our drivers ed car was a full-sized, made-of-real-steel 1974 Dodge Monaco, a glorious goldenrod color. My classmates and I were amazed that the school district trusted us with a brand-new car when we started driving. Living in the agrarian-based, blue-collar small Kansas town of Pawnee Rock (pop. about 350 in the1970s), some of us came from the land of hand-me-down vehicles with pre-dinged fenders. Therefore, an unmarred car with a mere 37 miles on the odometer made our steering wheel grip a bit tighter.

Mr. B., our drivers ed teacher, was a husky, recent college football player. When it was believed during that summer of 1973 that our high school, after a year of being closed, would be reinstated by U.S.D #495, Mr. B. was hired to be the high school football coach.

Unfortunately, Pawnee Rock High School was not resurrected, leaving Mr. B. stuck with us. Rather than coaching a full team of athletic stars, who had transferred the year before to other high schools, Mr. B. coached junior high boys football and girls basketball, and he taught drivers ed, and ninth grade physical education.

While everyone in town was devastated that our high school was gone for good, my classmates and I found a bright side in the story – we, as ninth graders, got to hang onto the P.R. experience for a bonus year. And that was because they had lined up Mr. B. and a few other teachers for the anticipated return of the high school which never happened.

The Rock, as it was called by locals, was the unique fingerprint for our community. Without it, Pawnee Rock would’ve been just another non-descript hard-luck town that went south following the high school closure (1972), later a closed junior high, and eventually no school in town at all. The Rock had always given us historic and geologic standing.

Located just north of the city limits, The Rock is an outcropping of Dakota sandstone, red-colored rocks jutting out of a hill, a high spot on the otherwise level land of the Arkansas River Valley.

The park has a narrow entrance gate of two pillars, made of Dakota sandstone (the stone was handy, I guess). If I were to estimate its size, the entire state-owned park is probably the equivalent of a city block.

A paved, one-lane road forms a tight circle around The Rock. The curve of the road is more open at the top, and then the downhill getaway is straight – at least until it jogs a few yards to the left, back to the narrow entrance/exit gate.

Our lifelong familiarity with this place clued us in on the challenge of backing around it. Knowing how steep the inside ditch was, I visualized our driver’s ed car at an angle to the road, back end stuck in the ditch, front tires hovering a foot or more over the pavement. Lordy, were we in for a ride.

The Rock had been our playground since the first time our parents took each of us up there and set us free. We knew every foothold, handhold, every climbable route. We knew that the loose sand on the rocks could make our leaps from one ledge to another a little tricky. Our fingers traced the names that had been carved into the face of every stone on that hill. We carved our own names. I always looked for “Kit Carson” etched in stone. Legend has it that Carson shot his own mule here, thinking it was an Indian.

This was a pretty place in the spring. Red stone, big blue sky, puffy white clouds above. The low-lying poppy mallow added hints of magenta to the sage-green buffalo grass. Spiky yuccas round the edges offered textural complexity to the scene.

Many of us town kids rode our bicycles up here for something to do on endless summer days. We’d chat with out-of-state tourists stopping through on their way to Colorado or to South Carolina, or to some other scenic state. Over the years, several visitors asked us where the Indians were. I don’t know what exactly they were expecting to find in the middle of Kansas in the late ‘60s, but the Indians in town were the Braves and the Warriors, our high school and junior high mascots.

Atop the Rock, on the flat base, sometime in the 1920s I believe, an open-air two-story pavilion was built from concrete and Dakota sandstone. On the ground floor, picnic tables provided a pleasant and shady gathering place for groups or families.

In each of the four corners were wide pillars of stone that held up the second floor which was accessed by a spiral staircase in the northwest corner. Once on top, you were greeted by the wind first, then the view, a sprawling vista. On good visibility days you could see the Burdett water tower, about 30 miles away, as well as towers in Rozel and Larned. To the southwest were Radium and Seward grain elevators. Dundee and the Great Bend airport tower were to the west.

Pavilion and monument atop The Rock

The Rock has always been a gathering place of sorts. Native Americans reportedly used The Rock as a meeting place and lookout point: it sometimes became a battlefield between tribes.

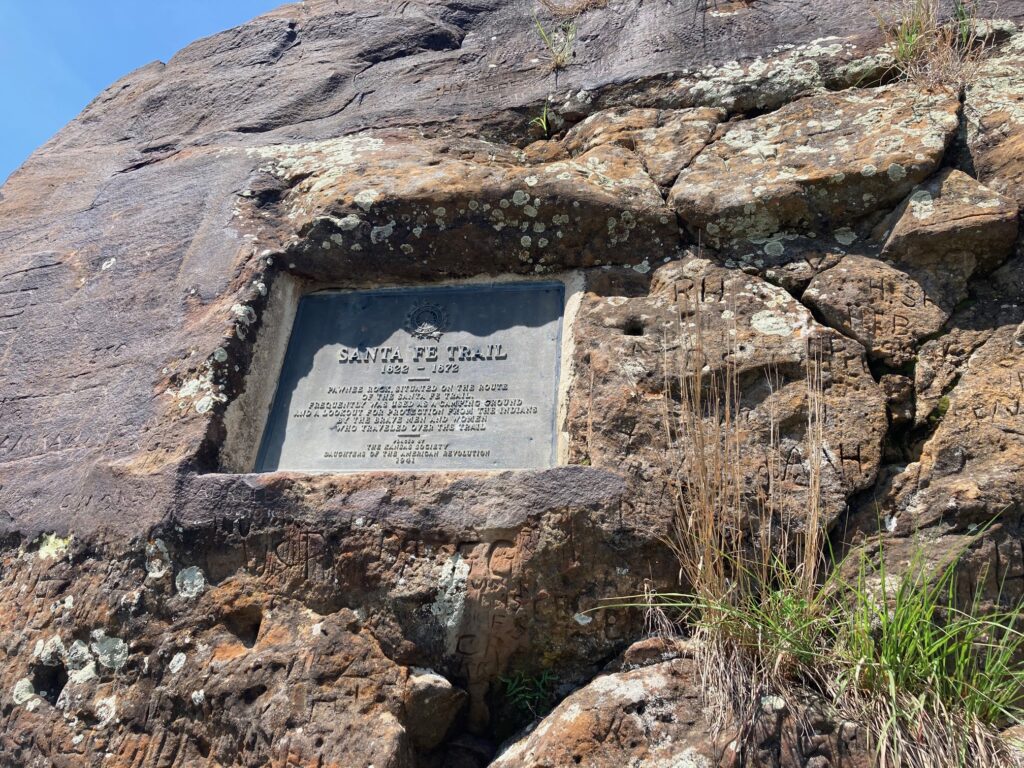

William Becknell opened the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 and Pawnee Rock was an impressive trail marker roughly halfway between Independence, MO, and Santa Fe, NM. Postcards in the 1970s proclaimed it to be “a famous lookout along the Santa Fe Trail.”

Bronze plaque commemorating the Santa Fe Trail

Matt Field, whose reporting was published in the New Orleans Picayune around 1840, wrote, “Pawnee Rock is a precipitous mass of stone, rising, with wild singularity, in the midst of a vast region of prairie . . . We were part of an afternoon, and the greater part of the next day travelling with Pawnee Rock in sight before us.”

Much of the Dakota sandstone was quarried and used for buildings in town or perhaps road material in the late 1800s as the town of Pawnee Rock was settled. To stop the dismantling of this natural landmark, the Kansas Women’s Day Club raised money and in 1908 the group purchased the land and turned it over to the state of Kansas for preservation.

According to geologists Jim and Susie Aber of Emporia, this geological feature is part of a layer of Dakota sandstone in the Smoky Hill physiographic region of Kansas that runs in part from Pawnee Rock into Ellsworth County, where it is observed at Mushroom Rock State Park; at Coronado Heights north of Lindsborg; and then north to a place called Rock City in the Minneapolis (Kansas) area where concentric stones are scattered randomly across a field.

As youngsters, we made good use of our geological friend. We hiked our sleds a quarter mile up to The Rock (no one would’ve ever had their mother drive them to go sledding), and then we slid down the straightaway road, sometimes also sliding down the tree-covered north slope.

Up until my 40s, when many of the north-side cedar trees were removed, I could locate the tree with the notch in the bark, the tree I had ridden my non-steerable sled into when I was about 8 years-old. The metal frame of the sled sliced a deep cut into the tree trunk. And as physics would have it, when sleds abruptly stop, objects lying on top of them keep moving. So, my body kept moving until my head hit the tree. The impact rolled me off the sled and I found myself flat on my back, lying in the snow, ice crystals tickling the skin on my neck between my stocking cap and my collar. This perhaps was my first concussion.

On my back for a few minutes gathering my breath and my brain. I could hear kids on the other side of the hill sliding down the roadway while I alone had selected this route through the trees. And most of the time it worked, slicing between the cedars. You had to bail off the sled before you got to the deep ditch because that ditch would wreck you for sure.

The Rock was a place for adventure when we were kids, but in my teens when I had a car of my own, it became a refuge of sorts. I’d climb the spiral staircase to the second floor, pull myself up onto one of the four 3-foot-high pillars on each corner and look out over the plains, unraveling my teenage angst.

On top of the world, I found comfort in distance. My eyes stretched to that horizon, 30 miles away. I had a half-globe of blue sky above me. Wind pulsed on my chest and in a strange way the sureness of those gusts felt like they could clear my body of whatever heaviness I carried inside.

At the end of my senior year at Macksville High, when I was selected by the eighth grade to speak at their graduation, I came to The Rock for solace. Looking south a mile toward the line of trees sheltering the Arkansas rivers, I climbed aboard one of those corner pillars, trying to psych myself up for the speech, the delivery of which terrified me more than backing around The Rock had three years before.

Monument at Pawnee Rock State Historic Site

It amazes me now, as I realize that Mr. B. was a very young man. Twenty-four years old. A kid, really. To us, he was an adult, a teacher, an authority figure. Perception of age is fluid though. When you’re in grade school, the high school kids seem like mature gods and goddesses. At the same time, anyone over 20 was considered old and unrelatable.

Mr. B. was a good-looking guy. He had thick and wavy golden-brown hair with a dominating-his-face 1970s mustache. And he had nerves of steel apparently. He didn’t ruffle easily, taking Donna’s verbal, and (possible) teenage-girl physical assault in stride.

On many of our driving days we headed west on US-56 to Larned, 8 miles away, and occasionally east on the same highway to Great Bend, 12 miles away, to practice highway and “city” driving. Larned and Great Bend had stoplights. And traffic.

Pawnee Rock had stop signs but most residents had yet to believe in them or subscribe to their cause. When I was in grade school, the city installed additional stop signs on side streets and I remember asking my dad the reasoning for them. “The stop signs show who is at fault when two cars run into each other,” Dad said. So, in other words, a way to assign blame to the inevitable accident that occurs because no one obeys them.

When we started drivers ed in August of 1973, the highway speed limit was 70 mph. In response to the Arab Oil Embargo which began in October of that year, the U.S. Congress adopted a National Maximum Speed Limit of 55 mph which took effect in March 1974.

Sammy Hagar voiced the opinion of many with his rock anthem, “I Can’t Drive 55.” The 55 mph speed limit lingered for two decades until a new law passed in 1995 returning the authority to each state to set their speed limits.

So, for at least part of our time in drivers ed., we drove 70 mph on the highway, which did and still does seem like a wildly high speed for brand new, 14-year-old drivers.

“I remember the time (Mr. B.) made me drive to Great Bend and pass on the highway,” classmate Jeanette recalled. “About halfway around the car, the song “Bennie and the Jets” came on the radio and he turned it up full blast. I don’t know how I kept (the car in the lane), but we didn’t have an accident.”

Mr. B. was not a wallflower. You knew he was there. And he loved the radio. If he liked a song, he turned it up; he sang along. Loudly. The hit by Ringo Starr, “You’re Sixteen (You’re Beautiful and You’re Mine), was also a hit with Mr. B.

Meanwhile back at The Rock, Donna, in the driver’s seat, had just completed the driving in reverse portion of our driver’s ed test. She was stressed and flustered, but she passed the test and passed the class.

“It was the last corner that I think I went off the road,” Donna told me in an email recently. “Mr. B. just sat there so calmly. He told me what to do and I got back on the road and completed the descent.”

“I still hate backing to this day,” Donna added. “I think it scarred me for life.”

It was then my turn to back the Monaco around this hill of sandstone. The car’s trunk took up the entirety of the rear-view mirror.

“I can’t see the road,” I said, using the steering wheel to lift my body, sweat sealing my thin cotton shirt to the car seat. Backing my way around the first curve at 4 mph, my right foot worried between the accelerator and the brake.

“Use your side mirrors,” Mr. B. suggested.

I made it, eventually.

We all made it. We all passed the class. The car survived, undamaged.

Mr. B. moved on to bigger and better things.

Our ninth-grade class, like those classes before and after us, split ourselves between four area high schools. While some of us stayed in touch with each other, it was heartbreaking to not share high school with half of my dear friends who knew me from the inside out, friends who could send me into gales of laughter simply by eye contact at an opportune time.

The Rock is a touchstone for those of us who loved that gritty sandstone mound; its form and structure remains an eternally-etched memory. The Rock was both a backdrop and a foundation for our lives. Even though our school was shut down in 1972, and the town’s population has greatly diminished, yet fifty years on, the spirit of Pawnee Rock remains fierce in us all.

-30-

The small town of Pawnee Rock is just south of The Rock.

East Side of the Rock

Recent Comments